Super-user sounds great, right? Who doesn't want to be super at something? Only this video (in Memphis-style) refers to the 5% of Americans that account for ~50% of health care spending in a year.

To paraphrase the end of the video: "There's almost nothing insurance companies won't charge, and Americans won't pay." How do you keep yourself from becoming a super-user? Everything medical is a matter of risk, so don't believe anyone who tells you there's a rock-solid simple way to keep from falling into that 5%, at least temporarily. But overwhelmingly, if you can keep a steady job you don't hate, if you can abstain from smoking, if you can get even a small amount of daily exercise (more is better, obviously), if you can keep your alcohol intake to a minimum, if you can abstain from recreational drugs (this includes marijuana, obviously), and if you can choose to eat mostly plant-based foods in semi-sane quantities, you're gonna stay out of The Five Percent.

What does excess immersion into video games mean for young men?

I've tried to set the Weeds audio above to play at about the 46 minute mark. But if that doesn't work, fast forward to the 46 minute mark. Not because the discussion of what "Trumpism" is isn't interesting (it is), but because the discussion that follows helped me think more deeply about the problem of excess immersion into video games that young people, especially young men, are experiencing. I've blogged about this before, and I talked about it at a recent speaking engagement. We seem to be creating a generation of youths who are increasingly isolated in very immersive video games, and then they're growing up into increasingly isolated and lonely people, particularly after age 40. As Ezra Klein says in the piece: if this were a problem of drug abuse, I think we would be acting collectively to do something about it. That's an apt comparison, since game addiction and drug addiction seem to have some physiology in common. But since the solution to technological problems currently seems to be "more technology," we are kinda-sorta just plowing ahead and hoping that video games fix themselves. I'm not optimistic. I think we need to start introducing programs to help kids moderate their exposure to video games and increase their exposure to the world at a young age. Dylan Matthews, who generally defends the idea of video games as a pacifying technology for people who can't or won't work, ends with this quote: "When we're in our eighties, we're all gonna be doing, like, flight simulator stuff. That's, like, how we'll spend--or, VR stuff, at least--that's what retirement's going to look like." Yuck. No. No. No.

A new meta-analysis shows that African-Americans who exercise may not derive the same protective benefit from type 2 diabetes as other races

(brief Healio write-up here)

I'm not ready to sign on to this point; race is a very blunt instrument when it comes to genetics. As the cost of gene sequencing falls, I think we'll not only be able to tease out drug effects in people with specific genetic features; we'll be able to more precisely target interventions like physical activity. Maybe certain people in this collection of studies would have benefited more from strength training, while others needed more endurance-oriented activities. Maybe some would have benefited from a specific combination of drug and activity. We don't know the answers to these things now, but we will soon.

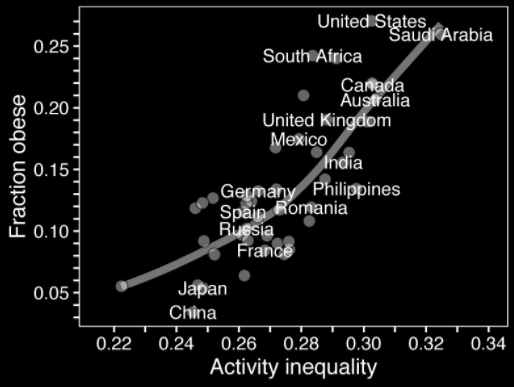

Smartphone data shows that countries with the highest "activity inequality" are more likely to have large obese populations:

More differences in activity within the population equals more obese people.

So it isn't a surprise that the same investigators found that the higher the walkability of a city, the lower the "activity inequality":

Texas is not a place with a great deal of walkability.

The cynical take on this study is something like, "Of course people who are inactive weigh more!" Fair enough. But the obvious policy implication of the study is that, to affect the activity level of the inhabitants of a city, the built environment must give opportunities for activity.