On a Saturday morning in November 2016, I woke up with a high fever and a frozen, excruciatingly painful right shoulder. I have a primary care doctor that I trust and like, but she, like most primary care docs, doesn’t work Saturdays. But I’m in the extremely privileged position of being married to a primary care physician (albeit not my primary care physician because that would be weird). My wife examined my shoulder, tsk-tsked my fever, and drove me to her clinic. One of her colleagues in the sports medicine department who happened to be in the building did a quick ultrasound of my shoulder and saw a possible effusion, or excess fluid, in the joint space, and recommended I be admitted to the hospital for a possible “septic joint,” the unglamorous medical terminology for pus in the joint space.

To make a four-day story short, I was admitted through the emergency department, went to surgery, had the shoulder drained, was seen by an infectious disease specialist who ruled out infection, continued to have fevers for a few more days, and left the hospital without a diagnosis, like around 15-20 percent of patients. But my fevers eventually subsided, and I healed up with the help of physical therapy. The problem hasn’t recurred.

I subject you to this story because I’m curious whether a modern insurance company would have considered my emergency department visit “appropriate.” I was clearly in distress. But to this day I have no diagnosis to explain my symptoms, and I can only assume that I would have eventually returned to my baseline state of health had I sweated out my fevers at home and taken over-the-counter pain medications for my shoulder.

But that’s all hindsight. My presentation really was worrisome for a septic joint, and when a patient presents with that diagnosis, we have maybe 24 hours to offer treatment before the infection causes irreversible damage.

United Healthcare, the largest health insurance company in America, decided a few months ago to start vetting emergency room bills, with the possibility of not covering a claim if the reason for the visit was not eventually deemed an emergency. Unsurprisingly, this caused an uproar not only among patients but understandably among doctors and hospitals as well. The doctors and hospitals don’t control who comes in the door, after all. They just take care of whoever walks in and try to cover the fixed costs of having a functioning 24/7 clinic open to the public. And as inefficient as emergency care can be, discouraging it could have the unintended consequence of diverting people away from needed care, and most patients already have a strong disincentive for ED use because of high-deductible plans and cost-sharing. And contrary to popular belief and the policy direction of many employers, Americans don’t actually overutilize care in comparison to patients in peer countries. So United Healthcare ultimately announced it would delay (but not abandon) implementing the new policy until after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed. (Anthem attempted a similar policy several years ago, but it is still tied up in litigation.)

On the other hand, though, it is generally accepted that the ED is a more expensive care environment than, say, a primary care doctor’s office. So if unnecessary ED visits could instead be diverted toward primary care visits, United Healthcare could save money and theoretically pass those savings on to everyone in the form of lower premiums.

So I was really interested to see Dylan Matthews’ analysis of the role of excess emergency department use in driving up healthcare costs. I cannot find a good link to his article; I got it via an email newsletter. So I’m going to do my best to outline his findings without committing outright plagiarism.

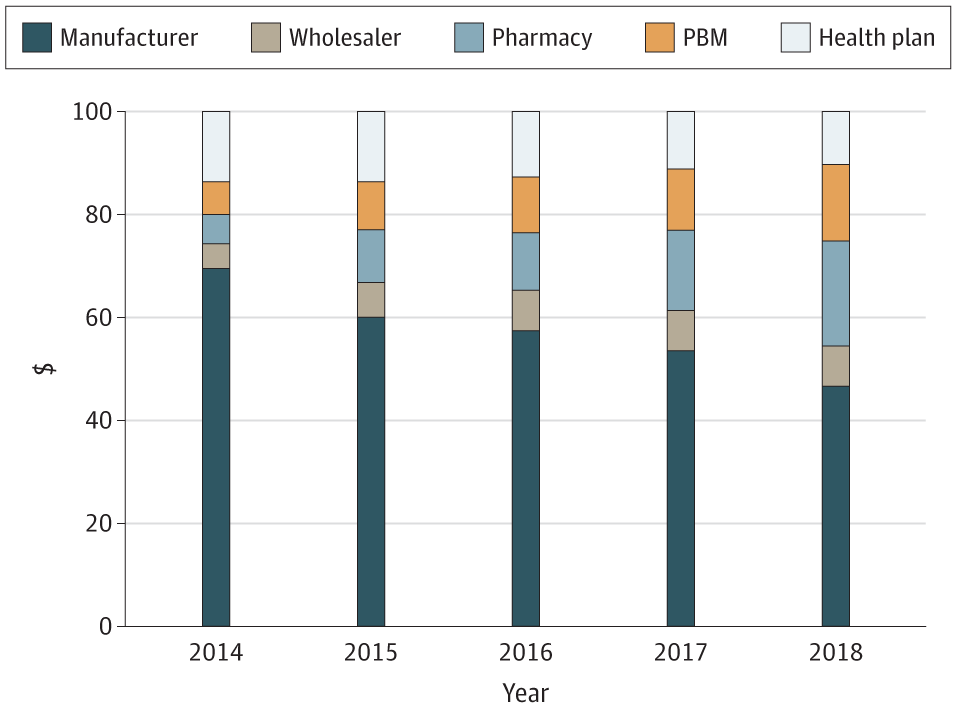

In short, Matthews found in speaking to a half-dozen healthcare finance experts from Harvard, Rutgers, and other institutions, that there is no evidence that reducing emergency department visits explicitly to save money actually works. This is, according to the experts, because rates of ED utilization have actually been steady for the last several years, and have actually dropped during and post-COVID-19. The problem with the ED, like with most of American medicine, is not utilization, but cost. And implementing a post-hoc vetting process like United Healthcare is proposing makes vulnerable patients the middle man in an astonishingly complex transaction. Some studies, like this one from 2017, show that incentives can provoke a small diversion toward primary care and way from the ED, but total costs don’t decline because the inpatient cost of the ED visit is simply shunted toward increased outpatient utilization. My personal caveat to this finding is that primary care is generally cost-effective in the long run, and that early intervention in the primary care setting is likely to lead to better outcomes. Short-term studies like the 2017 paper above don’t have the duration to detect this.

UHC and Anthem will presumably, sooner or later, get these policies going, and that will kick off a natural experiment that eventually tells us whether the policies do what they’re intended to do--decrease cost by decreasing ED use--or whether patients are harmed. What we unequivocally know is that the policies will lead to patients trying to decide if their problem is really an emergency. Is that chest pain because of your extra fries at supper, or is it a heart attack? Is that shoulder pain and fever a mystery that will never kill you, or do you really have a septic joint? It’s too early to predict what the effect of this will be. In the meantime, though, as we’ve mentioned many times before, the best way to optimize your employees’ care is to make sure they have good, low-cost access to a primary care practitioner.

We hope that insurance companies and other players in the health care marketplace can come up with more innovative ways to control cost, like addressing the outrageous prices charged for services compared to other countries, and spare patients the task of being their own health care providers and worse, small-claims adjusters.

As the Medical Director of the Kansas Business Group on Health, I’m sometimes asked to weigh in on hot topics that might affect employers or employees. This is a reprint of a blog post from KBGH.